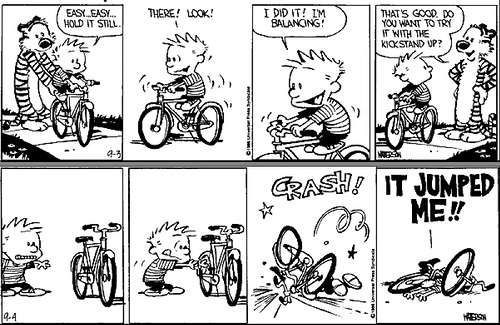

If you learned to ride a bicycle, there’s a pretty good chance you fell.

And fell down a lot.

I sure did.

What’s worse is I learned to ride on hills, with red mud.

And that means there was a good chance of losing control on the slopes. And grazing your feet, hands and face rather badly.

Plus I rode in the age without helmets. And without all those fancy shin guards, and knee-guards.

Logically, I should have never learned to ride a bicycle.

Logically, the lack of balance should have driven me nuts.

Logically, the number of band-aids and bandages should have made me give up.

Logically, my brain should have figured out, that the bike was trying to kill me.

But like you, I had a bicycle moment

For days on end, there was no respite from the falling.

Then suddenly in one second, I had a moment: The Bicycle Moment.

Suddenly I could balance. Suddenly I could ride. Suddenly it didn’t make sense why I was struggling so much.

Bicycle moments are seen everywhere.

Benjamin Zander, conductor of the Boston Philamornic Orchestra, talks about the fact when he got a pianist to stop playing on ‘two buttocks’. And got the young pianist to lift ‘one buttock.’ And there was a gasp from the audience.

You see the pianist had already practiced enough.

He’d already fallen many, many times.

But when that ‘one buttock’ moment arrived, it was his ‘bicycle moment.’

From that moment on, that pianist was no longer the same person.

But there are several issues that stop us from reaching the ‘bicycle moment’

- Issue 1: We don’t get an A grade in advance.

- Issue 2: If we are given an A, then what’s the need to improve?

- Issue 3: The tiny critiques set us back. Make us nervous. Less prone to risk—and more prone to never reaching our potential.

So let’s look at each issue separately

Issue 1: We don’t get an A grade in advance.

The reason I learned to ride a bike, is because all my friends could. It wasn’t like I needed to play Chopin’s Prelude No.6.

Every kid around me was having fun racing down the road on their bicycle.

It would be silly, even stupid for me not to learn how to ride.

My father could ride a bicycle. So could my mother. So could my uncles. And my grandmother.

Man, if there was talent in my family, it was bicycle riding, eh?

So I had an A in advance.

I had to ride. So I did.

But more importantly, I was expected to ride. It’s not like my parents, friends, and critics said, “You’re not genetically supposed to ride a bike. You’re not talented enough.”

You’d sound like a dope if you told someone something like that.

But look at what they do when you sit down to learn a skill.

They say: “Our family doesn’t have a mind for business. Our family can’t draw a straight line. Our family can’t do this, and can’t do that.”

Like hell you can’t.

There’s no family that’s genetically developed to achieve any skill. Not a single family on this planet. And yet, family after family happily hops onto a bicycle and rides away. Isn’t that amazing?

So if we know that we’re going to be able to achieve the grade, then hey, magically we achieve it.

Issue 2: If we are given an A, then what’s the need to improve?

Good question. Because we know for a fact that humans are lazy.

Now there’s one thing that trumps laziness. It’s called pride.

Your ego is bigger and stronger than laziness. In a boxing match, your ego would KO laziness out for the count in thirteen seconds.

When teaching someone something, you never appeal to their sense of achievement.

You appeal to their sense of ego.

And again, to reference Benjamin Zander…

He decided to give every single student an A. No matter what they did during the year, the student would get an A. Of course, this seemed unfair. Should the slacker get an A, even though another student has put in ten times the effort? But there was a catch.

The student had to write a letter to Benjamin at the start of the year.

The student has to say how the year would pan out, and why the student would deserve the A.

And the letter had to be handed in at the start of the year, explaining in full detail how the year would look. And why they’d end up as an A student.

Ego kicks in.

It’s why kids learn to cycle despite the falls.

If my friend can learn, so can I. I’ll take the grazes and the wounds, and get right back on my bike, thank you.

Using ego as a tool sounds almost too simple to be true. But hey, it’s true.

And sure, ego leads to over-confidence. And there’s where a mentor comes into play.

A mentor who critiques enough, but not too much.

Which takes us to the third issue: The tiny critiques set us back. Make us nervous. Less prone to risk—and more prone to never reaching our potential.

How do we not let the critiques drive us crazy?

It’s the mentor that’s always at fault.

Mentoring is a skill that needs mentoring. As teachers we need to go to the right ‘teaching school.’ But few of us ever do.

And so we don’t learn how to teach our students.

But here’s how students learn.

Students are like three-year old kids.

They can only grapple one letter of the alphabet at a time.

As a teacher, you can see the entire alphabet. Write it out. Understand the grammar. Understand the subtelties of the language.

The student can’t.

To them, the single letter of the alphabet is like climbing a mountain.

So when we knock the student off that mountain, it’s shattering to their ego.

This is more in the case of adults than kids.

Kids are like bicycle-riders. They don’t care.

Adults are wimps. They feel hurt, upset, angry, frustrated.

As a teacher, we need to understand this concept of ‘each letter of the alphabet.’

We need to get the student to work on one tiny part. One little part of the mountain. And then the next and the next.

But inevitably, we’ll run into impatience.

So we need to prepare for impatience in advance.

The student needs to write the ‘letter’ to us in advance.

The letter should outline that they’ll learn in little bits; master than bit; then move ahead.

The ego has kicked in again. Now they’ll want to live up to the letter.

They’ll know that climbing the mountain is hard work, but they’ll do it because they’ve promised to do it.

In little bits.

The more confident they get, the faster they’ll climb.

Then the critiques will seem like just another dumping of snow. Not an avalanche.

This is the core of what makes the ‘bicycle moment’ work:

1) The A Grade in Advance

2) The usage of ego in training.

3) Tiny bits of training. And mastery of those tiny bits.

It’s how I learned to ride a bicycle.

It’s how you learned to ride a bicycle.

And how we all have our bicycle moments.

Feel free to ask questions.

I do want to answer them 🙂